Many times during Super Bowl XLVIII, Denver Broncos quarterback Peyton Manning will stare down the NFL’s top-ranked defence, with five of his linemen the only things separating the future Hall of Famer and his surgically fused neck from a high-speed collision.

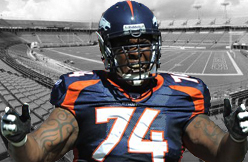

Six-foot-seven, 320-pound Canadian Orlando Franklin is one of those large men who will protect Manning from the onslaught of Seattle Seahawks pass rushers. At his size, Franklin can often shove aside defenders without trouble.

But the 26-year-old right tackle’s journey to the NFL has not been so easy.

Franklin was raised in the Scarborough area of Toronto, spending part of his time there living in a community housing complex. With his single mom, Sylvia, working to pay the bills, Orlando spent much of his time with the other kids in the neighbourhood.

When he was nine, Franklin spotted some kids carrying football equipment. One of them was an older boy named Shawn Williams, who brought Franklin to the local Scarborough Thunder football team, where he would become a mainstay until leaving for the United States in his mid-teens.

Williams remembers Franklin as tall for his age, clumsy, awkward and cursed with thick-lensed glasses he was often teased about.

One time, the pair had to search extensively for the expensive eyewear after Franklin lost a lens at a local pool .

"His glasses would get banged around [playing football], so his lens would pop out at any given time,” Williams chuckles.

"They drained [the pool] and they still couldn’t find it, and they drained it again and they finally found it. It took almost two days for us to get this lens.

"He couldn’t see for days… He was walking around with one lens in the glasses and the other one out.”

'Good kids'

The two became friends and would sometimes get into trouble together.

“We really had no money,” says Williams. “You would want to get food, talk to girls, so we would get in trouble. …stealing cars, trying to be cool, stuff like that.”

Charles Wiltshire, 54, who saw himself as a father figure to Franklin and often looked after him and Williams, says local kids often fall victim to the conditions of poverty.

"You realize they’re good kids, they’re not troubled kids. They don’t want to steal, they don’t want to rob, they don’t want to sell drugs, but they’re left with no choice to survive.”

In his early teens, Franklin was arrested for robbery and Wiltshire says that he bailed him out, like he had for many other kids in the neighbourhood.

“[My wife and I] were the type that if it involved drugs we would bail them out, if it involved weed we would be upset, if it involved guns we would have nothing to do with that,” he says.

'The first one to make it'

“I was in a real dark place,” Franklin told the Toronto Sun before last week's AFC championship game. “I mean, the NFL? Hey, I didn’t even know if I’d ever graduate high school, let alone think I’d ever make it to the NFL.

“At the end of the day, I could not see where my future was or where I was at."

But the trip to jail seemed to be the sobering lesson that motivated Franklin.

His head coach with the Scarborough Thunder, Roberto Allen, says Franklin agreed to sign a contract with his mother saying that he would stay out of trouble.

Allen soon saw a change in Franklin's performance.

“That last year when he played with us he was very focused,” says Allen. “He grew, he wanted this. He kept saying to me, I’m going to be the first one to make it.”

“For a big boy like that, he’s pretty athletic. He can run downfield with running backs. Usually offensive linemen are blocking at the first level and second level, but he goes up to the third level — he’s running downfield blocking defensive backs.”

With Franklin starting to turn things around at home, his mother went looking for work in Florida in hopes that she could move there with him to increase his chances to advance in his football career.

"I owe so much to my mom," Franklin told the Toronto Sun.

“When I said I wanted to move to Florida, she quit her job and moved down there a week later. You have a lot of parents who want to see their kids succeed, but you don’t have a lot of people who pick up and relocate just to accommodate a 15- or 16-year-old kid.”

Franklin ended up securing a spot at Atlantic Community High School in Delray Beach, Fla., and as a senior he attracted interest from the University of Miami football team.

'I can't take it'

Things didn't go smoothly at first in Miami. Wiltshire recalls how Franklin would call him when he was struggling to keep up with the Hurricanes.

“I remember he called me from Miami and said ‘Charlie I’m quitting this thing, I can’t take it no more, I’m puking my guts out, they’re working me like a horse, and we have to keep up certain marks in order to go and play.'" Wiltshire says.

But Franklin preserved and, after four years at Miami, where he was an All-Atlantic Coast Conference second team honouree in his senior year, he graduated with a degree in psychology.

In 2011, Franklin was selected by the Denver Broncos in the second round of the NFL draft (46th overall).

Wiltshire was with Franklin in Scarborough during the draft and remembers how Franklin jumped in excitement when he received the call from former Broncos quarterback (and now vice president) John Elway, one of his childhood idols, telling Franklin he'd been drafted.

Franklin still returns to the community, and has even showed up at a Scarborough Thunder practice to speak to the players and sign memorabilia for auction.

No matter the result of the Super Bowl in New Jersey on Feb. 2, those who helped Franklin along the way will still be proud of the kid with the thick glasses.

“My definition of a champion is not the one who won the race, but the one who tried his best to win the race," says Wiltshire. “And no matter what, he’s still my champion because I know he’s given his all.”

(cbc.ca)