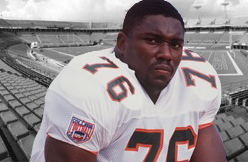

Football provided centre Brett Romberg with an athletic scholarship to the University of Miami, a rock-star college lifestyle and a lucrative NFL paycheque for nine seasons.

But it did so at a price.

Romberg willingly left football this off-season to work with former Hurricanes offensive linemates Joaquin Gonzalez and Toronto's Sherko Haji-Rasouli at a Miami tire distribution company. But the 32-year-old native of Windsor, Ont., is convinced the years of 'bangin' ' have left him with a degree of brain trauma.

"There's no doubt in my mind," Romberg told The Canadian Press via telephone from Miami recently. "Honest to God, I can't remember so many things.

"Game scenarios? Don't remember them. I have few memories of high school or playing junior football for AKO Fratmen (in Windsor), my memory is foggy about stuff like that. Times in college, games we went to, bowl games . . . I don't even remember.''

And that includes how Miami systematically dispatched Nebraska 37-14 in the 2002 Rose Bowl to capture the U.S. college football title.

"All I remember about the Rose Bowl is walking off the field with a Canadian flag stuck in my shoulder pads," Romberg said. "For Christ sake, my whole family went out for that game and I don't remember being with them, nothing.

"So there's no doubt in my mind there is some damage. I can't pinpoint it, obviously.''

Lawsuits from thousands of former NFL players have been filed south of the border this year against the league accusing it of hiding information linking football-related head trauma to permanent brain injuries.

Romberg has experienced more than just memory loss.

"Yeah, I go through states of depression too,'' he said. "I don't know whether that's common and everybody goes through it or is it something that is related to football?

"I have no clue. There has to be something going on. Regardless of how many concussions you've had, I think that does have an impact on your head with all that bangin'.''

Surprisingly, that's what Romberg misses most about being out of football.

"It's drudgery when you're playing and it's tough to go out in full gear Wednesday and have to hit after a Sunday when you got the crap kicked out of you," he said. "As much as you hated it, though, you definitely liked to get that feeling when you're popping somebody in the mouth because there's really nothing like it.

"The locker-room comradery is also something you can't find in corporate America. I got involved in this (with Gonzalez and Haji-Rasouli) because it's probably the closest thing I can get to a locker-room without getting a sexual assault charge or some kind of HR problem.''

Romberg was among Atlanta's last cuts last year but rejoined the club shortly afterwards and completed his second season there. While convinced he can still play — he said he has fielded offers from several clubs — Romberg felt it was time to get on with life after football.

"My wife ended up staying in Miami and working last year and it was tough having her fly every weekend to wherever we were at to see me for a few hours, then go back about her business here,'' Romberg said. "It was crazy.

"I also ended up missing my brother's wedding in Windsor and had to have the Falcons film crew do like a nice film that they ended up playing at the reception.''

The challenge of a new career — running the Canadian division of Tire Group International — and being able to settle into a new house with his wife, Emily — a corporate real estate lawyer in Miami — with plans to start a family soon made it easy for Romberg to turn his back on the almost US$1 million he'd earn this season as a 10-year NFL veteran.

"Yeah, it's a lot of money but I just realized after taxes and everything, $500,000 isn't worth disrupting what I have going on now for maybe a year and burning any bridges I might have in the business world,'' Romberg said. "And then there's possibly scrambling my eggs worse than they are, blowing a knee out and being in a cast and going through rehab and never having the same feeling in my appendages.

"And then, obviously the older you get the more painkillers you have to take and the more and more you rely on the pills and drugs to kind of get you through the week as opposed to your body the way it felt when you were a lot younger.

"A half-million bucks isn't going to change the way I'm living. I'm going to be 33 years old and if you had told me 10 years ago that I'd be playing in the NFL until I was 32 I would've kissed you.''

After a stellar tenure at Miami, Romberg signed as an undrafted free agent with the Jacksonville Jaguars, spending time on the practice roster before being promoted to the active roster.

Romberg remained with the Jaguars until 2006 before joining the St. Louis Rams and playing there until 2009 when he signed with Atlanta. Overall, he appeared in 44 NFL games, starting 18.

In college, Romberg helped Miami reach two NCAA title games, winning one, and also received the Rimington Trophy as the NCAA's top centre. He was a finalist for the Outland Trophy, given annually to the top lineman, and was named a consensus first team all-American in 2002.

He started his final 37 college games and never surrendered a sack. Off the field, Romberg was a larger-than-life figure for his punchy anecdotes to reporters, gregarious personality and willingness to do just about anything once, including pinching opponents' bottoms during games.

Prior to Ohio State's 31-24 double overtime Fiesta Bowl win over Miami in the NCAA title game Jan. 3, 2003, Gene Wojciechowski of ESPN The Magazine called Romberg "the best Canadian import since a case of Labatt's Blue.''

Teammates weren't immune, either, as Romberg earned a well deserved reputation of being a practical joker.

"Oh yeah, I had a lot of fun but life is so much bigger than football," Romberg said. "Life in the NFL is phenomenal, it's a great life and I wouldn't have changed it for the world.

"But it's a fairytale, an absolute fairytale. The reality check you get when you're done is a little bit different.''

Two years ago while with Atlanta, Romberg remembers experiencing a reality check in Tampa while out for dinner with the other offensive linemen.

"We're playing credit card roulette for a $1,500-$2,000 meal and it's no big deal,'' Romberg said. "I'm sitting there looking at the young waiter serving us who couldn't have been more than three or four years younger than me and this guy is making a living doing what he needs to do in order to survive.

"Now, we're not necessarily lucky because we did sacrifice a lot to get to where we were but I put my knife and fork down and was like, 'Do you guys realize that: How does what we do change anybody's life? You have doctors who save people's lives, you have policemen, firemen and military people who are putting their lives on the line for us and we're playing a game, we're getting paid more than any of those people and getting paid and we're not really doing anything more than giving that guy who works 40-50 hours a week something to watch Sunday.'

"It's a Catch-22 in my eyes.''

There's plenty the six-foot-three, 260-pound Romberg — down roughly 40 pounds from his playing weight — doesn't miss about football, like training camp and the physical toll it takes on one's body.

"I might be 32 but I don't have an average 32-year-old's body," Romberg said with a chuckle. "I've got problems with my shoulders, my back and my ankles.''

But all that pales in comparison to Romberg's disdain for the politics of the game.

"These GMs have to justify their (draft) picks," Romberg said. "Be that by giving a free-agent guy one or two reps in a pre-season game but giving a third-rounder a couple of quarters because they have to find a way to make it a reality that this guy has to be on the team because he was drafted.

"And it happens more than the public knows. Hell, half the centres that were drafted in my year were gone after the second year. It's a numbers game and you look good on paper and that's what brings you in the door and then your draft year keeps you there for a year or two depending on how high you were. After that you kind of become a lost commodity.''

Romberg admits the business side of the game has drastically diminished his love for it.

"I think it probably gutted it the moment I got into the NFL," Romberg said. "There's no doubt in my mind the business aspect of football just tears at the fun because it's no longer a game.

"It's actually your job, it puts food on your plate and young guys don't realize that until their third or fourth year when they start getting cut because they can get a younger guy who's a little bit cheaper and you have to do something pretty productive or pretty special that the young kid can't do.

"Luckily I always had a good offensive line coach for the majority of my career. My big slogan by the time I was in my sixth year was, 'You're only as good as your coach wants you to be.' ''

However, Romberg remains very appreciative of the opportunities football has afforded him.

"It's definitely a blessing,'' he said. "The doors the NFL has opened for me, the friends I have now in the music business and in Hollywood is all stuff a kid from Windsor would never, ever get an opportunity to do outside the fairytale of being in the spotlight and is very special.

"It's been a relatively smooth transition being able to basically end it on my terms and not because of a devastating injury. And with my job I've been to Canada more in the last five months than I have the last five years and it's good to see my family more often.

"I know I could still play and do what many of those guys are doing Sunday. But the question is: Does my body want to do it and do I really want to do it anymore? I have that opportunity in my life to do something with my mind rather than my body and possibly get my family started and settle down. That's more of a priority.''

(globalregina.com)