For most people, there would be something terrifying about the controlled violence of professional football.

For New Orleans Saints tight end Jimmy Graham, however, all the scary stuff happened off the field.

And most of that happened years ago when, at the age of 11, he awoke at the end of a car ride and discovered his mother was signing him into a group home. She dropped him off with two sacks of clothes, and with his sister wailing in the back, drove off into the night.

"Waking up in a place you don't know, with people you don't know, getting beat up every day -- it sculpted me," Graham said last week during the Saints' rookie camp. "It's definitely been a travel. I battled, but it's made my character."

He's also made an interesting group of friends during that travel. From Rebecca Vinson, the nurse who eventually took him in, to Donna Shalala, the president of the University of Miami where he spent five years as a student-athlete, something about Graham's personality drew them into his orbit.

It's not every scholarship kid, for example, who gets Bernie Kosar to throw passes to him three days a week when he wants to switch from basketball to football.

But, as Shalala noted when singling Graham out for praise when he graduated from Miami in 2009, sometimes a scholarship kid doesn't pan out, and sometimes they prove to be a man like Graham.

"He is a bright, special young man, with a joyful demeanor that is unusual and endearing," Shalala wrote in an e-mail Friday.

Praise from the powerful isn't taken lightly by its subject.

"That meant a lot, especially coming from where I'm from," Graham said when asked about Shalala's stamp of approval. "And I'm going to prove to her she made the right decision."

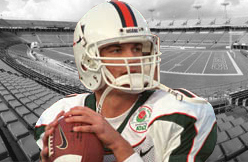

To see Graham, a chiseled 6 feet 6 and 260 pounds, is to see an athlete. He finished a four-year basketball career for the Hurricanes with more personal fouls than field goals, but he was also captain his senior year and could have played the game professionally in Europe.

Instead, he returned to what he called "his first love," football, for that fifth year of collegiate athletic eligibility, and the first time since he was in ninth grade.

Actually, he had wanted to play football at Miami before that, but the basketball coaching staff, understandably worried about injury, talked him out of it. Miami tight ends coach Joe Pannunzio insisted he was unaware of that early desire on Graham's part, but said the Hurricanes football coaches always loved to watch him play hoops.

"To be honest, and I don't mean to knock the sport, but basketball isn't as tough as football," Pannunzio said. "There has to be a part of you ready to get wiped out in football, and you have to have that mentality, and you could tell watching Jimmy Graham on the basketball court that he had that mentality. Right away we could see he had something we didn't have."

Whatever that right stuff was, Graham started developing it in that group home where his mother left him for two years. Graham still has never met his biological father, and he doesn't call any of the tough cases he met in the group home siblings.

He rejoined his mother and a man with whom she was involved -- Graham rather haltingly accepts the title of stepfather from him, although he found the man a snake from the beginning and was not surprised to learn he was cheating on his wife.

It was at that time, in Goldsboro, N.C., that he came to the attention of Becky Vinson, whose Bible study class Graham used to attend Wednesday nights, dressed in mismatched shoes and often soiled clothes, Vinson recalled.

"Then one week he spoke up, " she recalled. "We were going around the room with prayer requests, which are usually for some sick grandparent or something, and when we got to him he spoke with a real sense of urgency in his voice, saying, 'I need everybody to pray for me, because I think my mom is getting ready to put me back in another home.'"

So Vinson took Graham into the trailer she shared with her 6-year-old daughter, Karena. It was not a match made in heaven initially.

"You know, he'd been in and out of a lot of places growing up, " Vinson said. "He had a lot of anger, a lot of those issues he had to work through, and for the first four or five months it was really tough."

It was his grades that cost him football, Vinson said, recalling she read Graham the riot act when he brought home a raft of F's on a report card. Unless he got off the gridiron and concentrated on academics, Vinson said, he would have to go back with his mother.

Graham's report cards quickly turned to A's and, Vinson said proudly, "not in some easy bunch of classes, either, but algebra, geometry, biology -- in smart classes he was getting all A's."

The classroom success went hand in hand with the basketball he was allowed to continue, and Graham wound up as one of the top 100 high school players in the nation and a scholarship to Miami to play in the ACC.

College athletic departments are filled with kids who have overcome a lot of obstacles, who have beaten long odds to excel at a sport enough to earn a scholarship ride. But even in that group Graham stood out, according to Pannunzio.

"It's not that coaches can't identify the qualities in a kid that will translate into success, " he said. "It's that you realize the pool of Jimmy Grahams in the world is very small."

Tight end is something of a glamour position with the Hurricanes, as the program has produced a bevy of NFL players at that position. Yet Graham immediately became a starter. He caught only 17 passes in that one season, but he scored five touchdowns and caught the eye of more than just Saints Coach Sean Payton and General Manager Mickey Loomis.

In fact, a number of NFL teams watched him closely at the Senior Bowl, where he arrived after working out together in Florida with none other than Tim Tebow, who also found Graham impressive.

Still, there were indications the Saints might be the team. When they represented the NFC in Super Bowl XLIV in Miami, for instance, Graham was a guest of the team at a practice. Saints tight end Jeremy Shockey, who also played at Miami, gave him words of encouragement in the locker room; linebacker Jonathan Vilma already knew about the new kid at "the U, " as Hurricanes players past and present refer to their school.

Both Shalala and Pannunzio now refer to Graham as an "ambassador" for Miami, although when he screamed himself hoarse at Super Bowl XLIV he was wearing black and gold rather than green and orange and cheering for the Saints as they defeated the Indianapolis Colts 31-17.

And yet, despite the signs something could be brewing between Graham and the Saints, the only person who caught on fully was Karena, now 15 years old.

"A lot of teams seemed interested, so it was hard to say, but my daughter knew the whole time it would be the Saints, " Vinson said. "I was at a restaurant when the word flashed the Saints had taken him, and I screamed so loud people were worried."

Both Vinson and Graham said the fit seems logical, given the player and the city have endured so much.

"That was one of the things I thought about right away about coming to New Orleans, " Graham said. "I know there are a lot of kids in the city who have lived through a lot, and that seemed like sharing my own experience with them would be a kind of destiny."

Graham talks like that, with the easy grace of a well-educated man with a clear vision of his future. It seems remarkable that there isn't a trace of anger or slang in his voice, or something guarded or hunted in his look, but Vinson said it's always been that way.

"I know it sounds crazy now, but I always thought he had a lot of potential, " she said. "I can't tell you I thought he'd be a professional football player, but I knew he'd be successful. It's because he's so smart and because I told him he can't do poorly, that that was unacceptable."

The challenge meant a lot to Graham. He talks now with his mother from time to time -- she did a tour in Iraq with the U.S. Army, which Graham respects immensely -- but he is wary about past relations and he maintains strict control over his inner circle, which includes a New Orleanian he roomed with at Miami.

"I've forgiven my mom, but I'll certainly never forget, " he said. "Becky, though, she means the world to me. She took me in and gave me an opportunity and now she's very excited I'm in New Orleans.

"People come at you from everywhere, " he added. "But I'm a strong guy and I surround myself with good people. That's where I'm at right now."

(nola.com)