Nothing is more inspirational this time of year than the pop of a well accelerated fastball into the cavern of a catcher's mitt -- so welcome after a long, cold winter that the fastball's usual antagonist, the hitter, is unnecessary to its drama. Such a sound is all the more inspiring when at its origin is a young arm, as full of promise as Chapter 1. The scene plays out this week in every camp in Florida and Arizona, at once prompting joy and fear from the club elders who watch them. For as they imagine young pitchers' success, they also must ask the question no one has yet truly cracked: How do we keep them healthy?

The question is particularly timely in today's game. A wave of young pitching has washed ashore. Last year more 25-and-under pitchers made at least 10 starts than any time in the history of the game (71), including a 69 percent increase from five years ago. In just the past 13 months teams have handed out contract extensions that bought out free agent years of young homegrown stars Zack Greinke, Jon Lester, Josh Johnson, Ubaldo Jimenez, Felix Hernandez and Justin Verlander.

This spring offers more potential stars: Madison Bumgarner with San Francisco, Brian Matusz with Baltimore, Stephen Strasburg with Washington and Aroldis Chapman with Cincinnati. Meanwhile, pitchers such as Rick Porcello and Max Scherzer with Detroit and Joba Chamblerlain with the Yankees, like Milo of Croton, bear the heavier burden on their shoulders of a second year of full-time starting duty.

The only task harder than a breakthrough season is trying to do it again. Breakdowns are almost inevitable in pitching, but difficult to see coming. The best we know is that the two factors that most elevate risk of injury are overuse and poor mechanics, which often are interconnected.

More than a decade ago, with the help of then-Oakland pitching coach Rick Peterson, I began tracking one element of overuse which seemed entirely avoidable: working young pitchers too much too soon. Pitchers not yet fully conditioned and physically matured were at risk if clubs asked them to pitch far more innings than they did the previous season -- like asking a 10K runner to crank out a marathon. The task wasn't impossible, but the after-effects were debilitating. I defined an at-risk pitcher as any 25-and-under pitcher who increased his innings log by more than 30 in a year in which he pitched in the big leagues. Each year the breakdown rate of such red-flagged pitchers -- either by injury or drop in performance -- was staggering.

I called the trend the Year After Effect, though it caught on in some places as the Verducci Effect. As I was tracking this trend, the industry already was responding to the breakdown in young pitchers. The Yankees instituted the Joba Rules. The Orioles shut down pitchers late in the year. Teams set "target innings" for their young pitchers before camp even began. Clubs sent underworked starters to the Arizona Fall League to build their arms to better withstand regular work the next year.

Still, by oversight, circumstances or old school "take-it-as-it-comes" thinking, teams continue to overload young pitchers, which is why the Verducci Effect is still in business, with 10 pitchers red-flagged for 2010. Imagine my surprise when I first ran the numbers and found two pitchers from the earliest adapters of the Year After Effect, the Oakland Athletics. How could they of all teams, I wondered, let Brett Anderson and Trevor Cahill take jumps of 55 and 54 1/3 innings in 2009?

"Oh, no," Oakland GM Billy Beane told me. "We didn't. We always keep an eye on the Verducci metrics."

Beane explained that Anderson and Cahill pitched for the 2008 U.S. Olympic team, so their innings jump was not nearly as large or as dangerous as their professional innings would suggest. Goodbye red flags.

"We always keep an eye on that, especially when we get to September," Beane said. "In fact, we backed off them in September [with extra days of rest and lower pitch counts] just because of that. They each wound up in the 170s in innings, which was perfect. They're right on track this year to go out and make 30 to 35 starts and throw right around 200 innings. We think that's the natural progression."

Peterson convinced Beane back in 1998 that young pitchers needed their workload to "staircase," with modest annual increases so the body could grow accustomed to, rather than be shocked by, greater work capacity. It was an idea that was not radical to road running or weight training, but was new to pitching. Beane is a proponent of the "only so many bullets" theory -- that pitchers have only so many throws in their arms -- so when Peterson backed up his theory with data, Beane, who by the next year was sitting on a gold mine of young pitching in Mark Mulder, Tim Hudson and Barry Zito, was sold.

"One thing I told Rick was, 'I can be sold if you give me information,'" Beane said. "I don't pretend to know the answer. Nobody knows. But this just makes sense. Given a choice between too much throwing at too young an age and being conservative, we'll always take the conservative route. Look, Hudson, Mulder, Zito . . . we took good care of those guys."

The reality is that the cost-effectiveness and durability of those three young starting pitchers defined what made those Oakland teams successful more so than all the attention given to finding guys with good on-base percentages. In their 15 combined individual seasons in Oakland (not including partial rookie years), Hudson, Mulder and Zito averaged 17 wins, 33 starts and 219 innings.

"With Rick, he did his homework, sold me on it and we're abiding by it," Beane said.

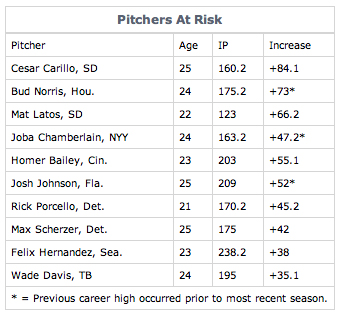

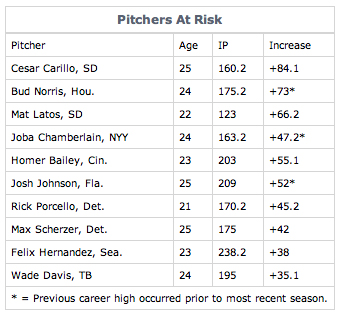

Of course, baseball is such a beautiful, analog sport that circumstance and 30 franchise cultures defy a one-size-fits-all philosophy. That's how I wound up with 10 young pitchers this year who fall into the danger zone. It's not a prediction that they will break down, but only an estimate that they are at risk of a fallback season because of an aggressive workload increase in 2009. Here they are, the 10 at '10 (includes all professional innings, including postseason and AFL):

In general, the younger the pitcher and the greater the increase the greater the risk. Likewise, the risk minimizes the closer guys are to the age and innings cutoffs. Here are thumbnail looks at the young pitchers at risk:

• Carillo, Norris, Latos: I hate to see guys with non-contenders getting pushed, as Kansas City and Pittsburgh used to do, but these guys have a common denominator: their previous workloads were depressed by injuries in minor league seasons. Carillo had Tommy John surgery, Norris suffered from an elbow strain (the Astros sent him to the AFL in 2008 and he still made the at-risk list) and Latos was bothered by oblique, ankle and shoulder injuries. The size of those increases remains significant.

• Chamberlain: Even with Yankees fans complaining about the Yankees treating him with kid gloves, Chamberlain made the list because he transitioned from a reliever into a full-time starter.

• Bailey: This is probably the most troubling case on this list, if only because there was no reason to lean so hard on Bailey down the stretch. The Reds finished 13 games out. In his last nine starts, Bailey averaged 112 pitches and was given an extra day of rest only twice even as he far exceeded his previous high in innings. The club kept leaning on him because he was pitching well, but to what end?

• Johnson and Porcello: These are understandable to a certain degree. Both clubs were playing meaningful games late in the season, when backing off one of your best pitchers is very hard to do. Porcello, because of his age, is more at risk of paying for the workload than is Johnson.

• Scherzer: Like Johnson, he took his increase at age 25, which minimizes the risk. But Scherzer bears close scrutiny because, like Chamberlain, his pitching health has long been questioned because of his throwing style. The Diamondbacks traded Scherzer in part because they never were sure that he would develop into the kind of workhorse starter that Edwin Jackson became in Detroit.

• Hernandez and Davis: They barely made the list, though Hernandez's innings do not reflect the two high-intensity games he threw in the World Baseball Classic -- once out of the bullpen.

At this time last year Mets pitcher Mike Pelfrey tried to convince me why he should not be on my 2009 list despite his 48-inning jump. He was a big guy, he said, who learned to be more efficient with his pitches. What happened? His ERA shot up from 3.72 to 5.03.

I try to stress that the effect is not a predictor -- it's just a guideline of risk. In the previous four years, I have identified 34 at-risk pitchers. Only four of them made it through that year without injury and with a lower ERA: Jimenez and three studs who did it last year, Tim Lincecum, Clayton Kershaw and Jair Jurrjens. (Jurrjens may not have escaped the effect after all. He reported to camp this week with a sore shoulder and will undergo an MRI to determine the extent of the problem.) Jon Lester, with only a slightly higher ERA in a fine 2009 season, merits mention, too. The at-risk pitchers last year who confirmed the effect included Pelfrey, Cole Hamels, Chad Billingsley, John Danks and Dana Eveland.

Past red-flag lists presaged the breakdowns of pitchers such as Jose Rosado, Chris George, Runelvys Hernandez, Dustin McGowan, Gustavo Chacin, Francisco Liriano, Anibal Sanchez, Fausto Carmona, Adam Loewen and Scott Mathieson. It's not perfect nor is it meant to be. But to borrow from Beane, given a choice, why not take the conservative route?

(cnnsi.com)