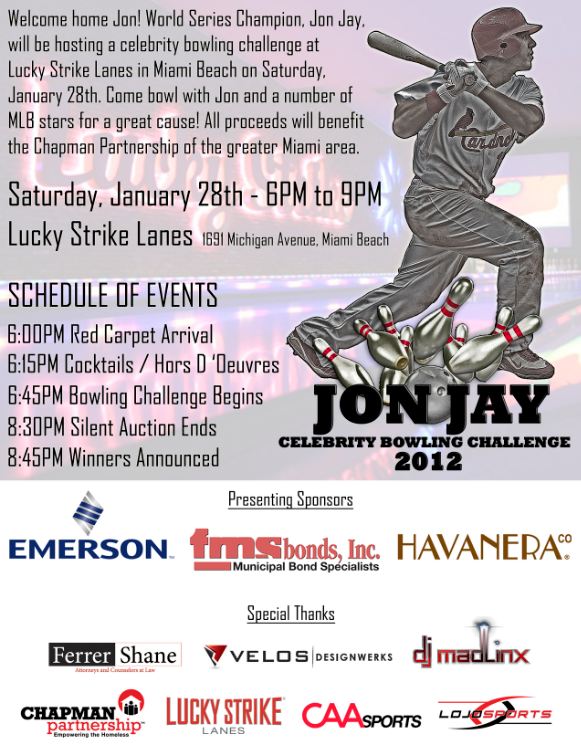

Vince Wilfork balances an abundance of excitement with equal measure of regret.

As the New England Patriots defensive mainstay prepares for Super Bowl XLVI, the four-time Pro Bowl lineman cannot help but mourn anew the loss of his parents, who died a little more than six months apart when he was a sophomore at the University of Miami in 2002.

He was so overwhelmed by the loss he wanted to quit the game.

Now Wilfork, 30, described by safety James Ihedigbo as the “heart and soul” of New England’s resurgent defense, prepares to lead the Patriots in a rematch of their 17-14 Super Bowl XLII loss to the New York Giants that prevented a perfect season.

“This is one of those games where I would love for them to be there with their 75 jerseys on. I would love for them to see their son play in the biggest game in history,” he said. “It doesn’t get any bigger than the Super Bowl.”

The stage in Indianapolis will reopen those wounds.

David Sr. died of kidney failure at 48 on June 2, 2002, after suffering from diabetes for many years. Barbara, 46, died Dec. 16, of complications following a stroke.

Wilfork, who is 6-2 and 325 pounds, has understood since then how important it is to make the most of every day, every opportunity. He plays every play as if it is his last. A tattoo on one arm reads: “One life.” On the other: “To live.” On one forearm: “RIP Mom.” On the other: “RIP Dad.”

He always was big for his age. He told his father when he was 4 that he would play in the NFL, a conviction that always was encouraged. As he grew up and began to excel on the field, he became more and more certain he would see that day.

And less certain his father would be there to celebrate.

His childhood was hardly carefree. His father was diagnosed with diabetes when Wilfork and his older brother, David, now 32, were in grammar school. The disease became increasingly debilitating.

While Barbara worked as part of an unending struggle to pay bills, the boys devoted time after school to make sure their father had his insulin. They made certain he was washed when he was too weak to help himself.

As sick as he was, their father always commanded respect. When Wilfork had academic deficiencies before he started his collegiate career, David Sr. saw to it that they were corrected. When the Hurricanes won the national championship in the youngster’s freshman season, the ring meant as much to the father as it did the son.

When David was gravely ill at Bethesda Memorial Hospital in their hometown of Boynton Beach, Fla., Wilfork rushed to his side to place that ring on one of his fingers. It would be the final expression of his love.

‘Everything stopped’

Although his father had been ill for so long, Wilfork struggled to cope with his death.

“My everything not breathing,” he said. “It hit me and it hurt me.

“I wasn’t ready for him to go yet, because I had plans. I was going to go to the NFL. I was going to get you in a nice house.”

It helped somewhat that, the night his father was buried, his girlfriend, Bianca, now wife of eight years, learned she was pregnant. They have three children: D’Aundre, 14; Destiny Barbara, 8; and David Dream Angel, 2.

Wilfork drew much closer to his mother in the next few months, only to receive two phone calls he will never forget. First, she suffered a stroke. Five weeks later, after she appeared to be recovering, she died from a blood clot to her heart.

“It was very unexpected,” Bianca said. “I think that’s what hit Vince the hardest. … To this day, we just say she died of a broken heart.”

Wilfork again found himself at Bethesda Memorial Hospital.

“It was like I saw my father all over again. They put my mother in the same exact room,” he said. “My mind was blown. Are you serious right now?

“It was like everything stopped. Nothing mattered in my life because the two best things going for me, not including my girlfriend, are gone.”

Without either parent in the stands, he wanted no part of football. Bianca spoke to him. His Miami teammates appealed to him as their national championship game against Ohio State in the Fiesta Bowl neared. There was no reaching him.

Finally, defensive line coach Greg Mark broke through. According to Wilfork, players had disrespected Mark for a good part of the season. He did not always watch film with them and appeared to be in a hurry to end his day.

Mark confided in Wilfork that his wife was battling cancer. He spoke of the need for both of them to persevere. He urged the grief-stricken sophomore to dedicate his play to his parents from that point.

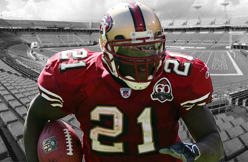

Perhaps that is why Wilfork, drafted 21st overall in 2004 and a factor when New England completed a run of three Super Bowls in four seasons that year, tosses other 300-pound men like rag dolls. Perhaps that is why he consistently commands, and often defeats, double teams that create opportunities for teammates to make stops.

Keeping them close

The eight-year veteran keeps a gold medallion, a gift from Bianca, which contains a photo of his parents that was taken at their high school prom. It constantly reminds him that all of his sweat is for them.

For the length of the game, that motivation turns a gentle, soft-spoken man into a rampaging lineman who refuses to allow anyone or anything to get in the way of a revenge-minded team that takes a 15-3 record into the Super Bowl.

“He is definitely two different people,” Bianca said. “For as aggressive, monsterish, what a beast, whatever you want to call him on the field, it’s the polar opposite at home. He cooks, he cleans, he changes diapers.”

Wilfork has never forgotten those hometown fans who dismissed him when he told them he would compete in the NFL.

“A lot of people doubted me. I love making people eat their words,” he said, his voice rising. “You do not tell me what I can or cannot do. If I put my mind to it, I can do whatever I want.”

He has enough fire to spur a defense that surrendered yards in chunks during the regular season (it ranked next to last in total defense with 411.1 yards and passing yards with 293.9) but has stepped up in the playoffs. First, a 45-10 rout of quarterback Tim Tebow and the Denver Broncos in the divisional round; then critical stops in a 23-20 thriller vs. the Baltimore Ravens in the AFC Championship Game.

“That’s our leader,” said Ihedigbo (ee-HEAD-dee-bow). “Him and (linebacker Jerod Mayo) are the leaders of the defense. We fall in and follow them from the first snap.”

As they followed him this season, Wilfork earned a third consecutive Pro Bowl berth. He finished the regular season with 74 tackles, a career-high 3½ sacks, eight quarterback hits, his first two career interceptions, one forced fumble and two fumble recoveries, including one in the end zone for a score in a 34-27 win at the Washington Redskins on Dec. 11.

With New York known for its ultraphysical play, New England will look to Wilfork, with his massive girth, to set a tone that will allow the Patriots to at least match the Giants’ muscle. One of the keys will be whether New England can handle New York’s solid offensive line well enough to exert pressure on Eli Manning, who joined the ranks of elite quarterbacks by passing for a franchise-record 4,933 yards.

Patriots wide receiver Julian Edelman, thrown into the mix in a depleted secondary, is confident Wilfork will be so disruptive that he will create pass-rushing lanes.

“He goes out there and leads by his actions,” Edelman said. “And that’s what you want in a leader: a guy who goes out there and makes plays. And that’s what Big V does.”

A prized Patriot

How much longer Big V does it for the Patriots is not in question.

New England is known for allowing high-profile players to leave rather than awarding them large contracts.

Wilfork? Coach Bill Belichick viewed him as a keeper, and ownership responded before the 2010 season by giving Wilfork a contract worth $40 million over five years with $25 million guaranteed.

Belichick, who emphasizes versatility, notes he can use Wilfork at any of the defensive line positions.

“I think the most important thing is just the way he goes about it,” the coach said. “He doesn’t talk as much as just demonstrate how to prepare, how to practice, how to do your job, how to communicate the different line calls.”

The Patriots monitor Wilfork for any sign of diabetes or other issues. He avoids fried food but acknowledges his weight tends to balloon to as much as 350 when he is less active during the offseason. He thinks his ability to shed pounds whenever he ends his career will be critical to his long-term health.

“I want to see what my parents didn’t see — grandkids,” he said.

This has been a particularly challenging season. Through it all, Wilfork called on younger teammates to have his type of mental toughness and keep the faith that it would improve.

“A lot of times he doesn’t get the attention he deserves because of that offense,” said former Patriots safety Rodney Harrison, a teammate from 2004 to 2008 and now an NBC analyst. “But they wouldn’t be in the situation they’re in right now without him.”

That gold medallion is sure to be with Wilfork when he arrives at Lucas Oil Stadium. He feels his parents will be there in spirit.

“They will have the best seat in the house,” he said.

(tucsoncitizen.com)