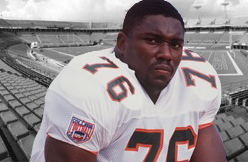

In his autobiography to be published next month, Warren Sapp does admit there is a play he made in his 13-year National Football League career he wished he could change.

But it isn’t the one in which he put a notorious block on Chad Clifton of the Packers.

In "Sapp Attack," the former Tampa Bay and Oakland defensive tackle wishes he could change the outcome of the tackle he made on San Francisco wide receiver Jerry Rice in 1997 that sidelined Rice for three months with a torn anterior cruciate ligament.

"I found out later that season that Jerry Rice was upset that I hadn’t called him at the hospital to apologize," Sapp says in the book he wrote with David Fisher. "Apologize? You don’t apologize for a clean hit. I had absolutely nothing to apologize for, but I was very sorry he was hurt."

In the book, Sapp is neither apologetic nor contrite about his hit on Clifton, a point of view he has held in the days following that game in Tampa Bay on Nov. 24, 2002 and has maintained in the years since.

Sapp tells the story of how his trash-talking rivalry with Packers quarterback Brett Favre began and continued, but for the moment, let’s keep today’s camera trained on the Clifton hit, which gained national attention at the time.

Sapp writes he received death threats because of that hit on Clifton during a game the Buccaneers won, 21-7.

The league determined Sapp’s hit to be a legal play and took no disciplinary action, but three years later made it a penalty for hitting a defenseless player.

In his account, Sapp writes that no hit he had in his career was any "bigger or more controversial" than the one on Clifton, but that "it wasn’t the hardest, it definitely wasn’t the hardest, but it was in the open field and got caught on TV, and people never stopped talking about it."

The hit occurred after Favre threw an interception, which cornerback Brian Kelly of Tampa Bay began to return.

Sapp went in search of someone to block.

"On television it appeared like I came across the field and blindsided Clifton, who didn’t even look like he was in the play," Sapp writes. "And then I did a little dance to celebrate that hit. That’s what it looked like. . . . Basically, the impression was that I had mugged an innocent bystander."

But those television images are misleading, Sapp contends.

When a defense intercepts, "instinctively the first thing you do is look for someone to block," Sapp says. "When the team is looking at the game films the next morning, trust me, everybody is going to be watching to see who got the biggest hit on the interception. If you don’t hit someone after an interception you are going to be called out in that room. So you learn to hit anybody – hit a vendor if you have to. But hit somebody."

Sapp says the first player he looks to hit on an interception return is the quarterback because "the protection he is granted by the rules is gone" and "it’s like Superman meeting kryptonite."

Sapp says "Favre took one look at me and started running straight for the sideline" because "he knew that the safest place for him was out of bounds, where he wasn’t going to get hit, and would survive to pass again."

Sapp says since he couldn’t block Favre he went looking for "the left tackle and then the center, in that order." Clifton was the left tackle.

"When Favre took off for the hills I looked for Clifton, and I spotted him on the side of field, but he wasn’t running, he was loafing after the play," Sapp writes. "I was disappointed. I had nobody to hit."

It is common among offensive lineman in the NFL to have self-imposed fines "for not being in the frame," according to Sapp.

"What that means is that when coaches are watching the game film they pause it when the player returning the interception is tackled – and every offensive lineman has to be in that freeze-frame," Sapp writes.

He does not say if the Packers’ offensive lineman had such a fine.

"Right after the interception Clifton was not in the frame – he was loafing," Sapp says. "After Brian made a couple of moves I figured Clifton had to be chasing him. That’s when I looked toward the sideline and saw him la-di-da’ing. The man was on the field of play in a National Football League game. He was a potential tackler. There is a reason my position is called defensive tackle rather than defensive blocker or defensive talker – my job is to hit people. So I hit him. Hit him good, the way I had been taught; the way he would’ve hit me if he had the opportunity. I saved Chad Clifton $1,500 for not being in the frame.

"People complained that he was out of the play when I hit him," Sapp writes. "Except that’s not the way football works. On an interception return the only people out of the play are on the sidelines or in the stands. If he was on the field, he was in that play. I didn’t realize I was supposed to be kind to him. He was loafing across the field. After I hit him I celebrated. . . . I did not know he was hurt when I celebrated."

Packers coach Mike Sherman’s decision to confront Sapp (left, credit: AP) about the hit as the teams left the field added to the play’s notoriety.

What did Sherman say to Sapp?

"Cheap shot, mother------."

"That’s not what he told reporters he said, but trust me, that is what he said," Sapp says. "He was lucky I wasn’t 25 years old without kids and a conscience. That would have gotten ugly. Instead I said to him, ‘What do you want to do about it?’ Members of security tried to get between us, and I warned them to keep their hands off me. I told Sherman, ‘Say it again.’ I moved toward him and he cowered away. ‘You trying to get me to punch you in the damn mouth?’ Oh man, I was overheated. I probably threw some other language in there too.

"The cameramen had come over to us, and Sherman wasn’t saying another word," Sapp says. "On camera he was going to be the good guy. I was livid. I said, ‘You’re so tough, go put on a jersey. C’mon, get some.’ I said a few more words and then walked away."

Sapp reminds readers that two Packers players were penalized for personal fouls during the game.

"Sherman told reporters he was reacting to my celebration, which he ‘perceived as inappropriate,’ " Sapp writes. "My response was much more reasonable, especially when I referred to him as ‘a lying, -----eating hound.’ Later their offensive line coach promised that the next time we played they were going to cut block me and injure me. Yeah, right, I thought, bring ’em on."

(jsonline.com)