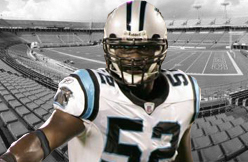

Watch any Carolina Panthers game nowadays and it is impossible to miss Jon “The Beast” Beason.

At age 23, the Panthers' middle linebacker has turned into a defensive star in his second NFL season.

His sideline-to-sideline speed, coupled with an uncommon maturity and a superb work ethic, have made No.52 a Pro Bowl caliber linebacker and the soul of the Panthers' defense.

To many of his teammates, Beason has become the Jake Delhomme of the defense, tapping into the same emotional extremes as the Carolina quarterback. “In my mind, Jon is the future here,” says nine-year Panthers veteran linebacker Na'il Diggs.

Beason's play prompts many teammates to recall the pre-injury work of former Carolina linebacker Dan Morgan, who like Beason was once a standout at the University of Miami.

Beason says he would like to eventually be compared to both Morgan and to the late Sam Mills, a former linebacker and assistant coach for the Panthers. Mills, who died of cancer in 2005, was known throughout his career as a ferocious player and dignified man. He is the only former Panthers player inducted into the team's Hall of Honor.

How Beason got to this point is a story threaded with hope. It includes a resolute single mother who banned the words “stupid,” “dumb” and “can't” from her house. It includes the older brother who inspired Beason, the high school coach who mentored him and the father who rarely saw him. Bill Belichick makes a brief appearance, as do Beavis and Butt-Head.

They all helped shape Beason into the player and man he is today entering Carolina's 1p.m. home game against the New Orleans Saints, who boast one of the NFL's best offenses with quarterback Drew Brees and running back Reggie Bush.

The Panthers trust Beason as a defensive team captain. He tells his teammates that he loves them before big defensive stands. He makes Delhomme laugh with an on-field exuberance that reminds the quarterback of himself.

“Jon is a guy who wants to be great,” Delhomme says. “And anytime he makes a play, he does a bunny hop. That's fun when you have somebody with life like that.”

On the field, Beason can be “on the verge of being out of control,” Diggs says.

Off it, he prides himself on staying in control and doing things right the first time. He's a young man of contrasts – one who has embraced Charlotte and says he can feel the city hugging him back.

For 23 years, Terry Beason has been Jon's mother, protector and guiding force.

“My mom is my backbone,” Beason says. “You think I'm good? She's the real overachiever in our family.”

Terry Beason didn't know what her boys were going to do when they grew up, but she knew how she wanted to raise them. As a single mother in Liberty City, one of the poorest sections of Miami, she fought difficult odds.

“I decided early on that I was going to make sacrifices for them, and I haven't really stopped,” Terry Beason says. “My whole life has been devoted to Jonathan and Adrian. My success stories are my children.”

On most mornings, Terry Beason rose at 5 a.m. and began cooking dinner for that night. The boys would put it in the oven when they got home from school. That way Adrian – the elder brother by 16 months – and Jon could always have a hot supper.

Once Terry finished supper, she moved on to cooking breakfast – a real breakfast. She would no more have sent them out the door with a single piece of toast than she would have let them mutter “yeah” instead of “yes.”

Then she would ferry both boys 25 minutes away to a school in Pembroke Pines rather than the neighborhood school in Liberty City, which she had judged to be inferior.

From there, she would drive to her own job in downtown Miami. “Mom wouldn't eat lunch sometimes so we could have an extra dollar to get ice cream in elementary school,” Jon Beason says.

Says Terry: “We didn't have a lot, but we tried to double up on character and love.”

The three of them lived with Jon's grandparents in Liberty City for roughly the first decade of the boys' life. On most Saturday mornings, the Beasons went to the Barnes & Noble bookstore to read. Terry Beason banned the boys from speaking the neighborhood slang.

Adrian and Jon received some teasing for the way they talked from their friends in Liberty City.

“They'd say we were trying to ‘talk white,'” Adrian recalls. “But it wasn't that. We were trying to learn how to present ourselves. You wouldn't go to church in your beach clothes, would you?”

Says Panthers tight end Dante Rosario, one of Beason's closest friends: “A lot of people like to think football players are dumb brutes. Jon is a very intelligent person, and you get that right away from speaking to him.”

When Jon was 10, Terry Beason took a leap. She moved out of her parents' house and moved with the boys into a condominium complex in a better neighborhood.

The condo was unfurnished except for a tiny TV mounted underneath a kitchen cabinet.

Both Beason boys remember turning on the TV and standing there, amazed, as “Beavis and Butt-Head” flickered onto the screen. They had heard about the MTV show, but had never seen it because they had never lived in a house with cable.

Their mother was strict about what TV shows her children watched, but relented for a few moments when she saw how awe-struck her boys were.

Beason still remembers it as one of the greatest nights of his life.

Then Terry Beason listened to the show's language for a while, smiled and said: “Turn it off.”

An inspiring brotherAdrian and Jon Beason sprawled on their bunk beds in their new condominium one evening, watching the Atlanta Falcons play. Suddenly, a Falcons player named Deion Sanders intercepted a pass, made a dazzling move and high-stepped into the end zone.

Adrian was hooked. “It was like I had this fire in me,” Adrian remembers, laughing. “I ran through the whole house, then into my mama's room. I said, ‘Mom, I want to play football!' ”

Terry Beason's reply was quick. You're not playing football, she said. You might get hurt.

Ten seconds later, younger brother Jon came sprinting in, as well, declaring: “Mom, if you sign Adrian up for football, you have to sign me up, too!”

No, Terry Beason said firmly. Nobody's playing football.

Both boys burst into tears.

But Terry Beason was tough. A few tears didn't change her mind. “She was very overprotective then, and she's very overprotective now,” Jon says.

For three weeks, the boys alternately dreamed of football and pouted about not getting to play.

Then Jon found a book in the school library that contained the ammunition he needed. It contained a single paragraph on the benefits of team sports and how studies had shown kids who participated in them usually did better in school, too.

Jon brought the book home and showed it to his mother. “He pleaded his case very well,” she remembers.

And so she signed the boys up.

For years, they played on the same teams. Jon was determined to keep up with his older brother, so he always played up one age group.

“The moment I knew Jonathan was the deal,” his brother says, “came when we were down by a TD and they put him in at halfback to run the halfback pass. He was about 10 years old. He rolled out to the right, planted and threw the ball at least 50 yards. It went to another kid for a touchdown. That's when I knew: he was ahead of his time.”

Adrian Beason wasn't small for his age, but Jon was big for his. “They were practically twins,” their mother says, “except in school, where I started Adrian early so he was two grades ahead.”

They played high school football together, too. Adrian was the first brother to get a full scholarship, to Fordham as a defensive back. He played there and earned his business degree. Although his career was slowed by a knee injury, he did play a year of Arena Football in 2008 in Albany, N.Y.

“Football is over for me now, though,” Adrian says. “I'm ready to get onto the next stage of life.” At age 25, Adrian Beason Jr. is now studying in Miami to get a teaching certificate. He plans to teach and coach high school football in 2009.

An absent father

Adrian Beason Sr. has flitted in and out of his boys' lives. His relationship with his son Jon has been spotty, and the two rarely talk these days.

“My parents were married once,” Jon Beason says. “They tried to make it work when I was really young, but it never got to the point of moving in together again. When I was about age 6 or 7, they just said, ‘That's it.'”

Adrian Beason Sr. has worked for years as a longshoreman at the Port of Miami, helping load and unload cruise ships. “We saw him about once every four to six months,” Adrian Jr. says. “When we saw him, it was more like he was one of the boys. He'd throw us some passes to us or something.”

Both Beason brothers say they didn't realize they were missing anything until they were older. But now Jon sees fathers who are close to their sons and longs for a relationship he never really had.

Sometimes, in the aftermath of a Panthers game, Jon Beason glances over at reserve linebacker Adam Seward visiting with his own parents. Adam Seward's father is a former college football player and coach.

“I watch them,” Beason says. “They tell funny stories to each other. His dad is really involved in how he does. That'd be nice, you know? I don't regret it. I'm stronger for it. But it would be nice to have both your mom and dad meet up with you after a game.”

A caring coach

Beason's life was deeply influenced by Mark Guandolo, his high school coach.

“I consider Jon a son,” Guandolo says. “I get choked up just talking about him.”

Guandolo then coached the private high school in the Fort Lauderdale area that offered Beason a scholarship in ninth grade. Beason played fullback and strong safety for Guandolo, never leaving the field and picking up his “Beast” nickname.

“Jon was our captain and our team leader,” Guandolo says. “He wanted to win so bad. That was always his motivation.”

In Beason's first season, before Guandolo came, Chaminade-Madonna was 2-8. By his senior year, the team was 14-0 with 11 shutouts entering the 2002 state championship game. They lost it, 6-0, and Beason has never quite gotten over it.

“It still eats at Jon,” Guandolo says. “He was devastated when it happened.”

Chaminade-Madonna would win the state championship the next season, without Beason. That eats at him, too, as does the fact that the University of Miami never made the national championship game when he played there.

Both Adrian and Jon Beason played for Guandolo. “He's just a great, great man,” Jon says. “He transforms kids. Stresses education. Lays down the law. And works you really hard.”

After one of Guandolo's intense practices, most of the players would collapse on the ground, aching and spent. Beason would go the extra mile, literally – running one final mile after practice concluded.

“He was a true beast in the way he prepared himself,” Guandolo says. “The nickname has always fit.”

The day after Beason signed a scholarship to Miami, he delivered a personal thank-you letter to members of the school's faculty and administration. “He never forgot anybody,” Guandolo says. “I'm sure his mother had something to do with those letters, but still. You don't see that much. He's special.”

A drink of waterRecruited as an “athlete,” Beason briefly played as a fullback at Miami, then switched to linebacker, where he found his niche. By the end of his redshirt junior year, he was a sure first-round pick. He promised his mother he would return to get his degree, then declared a year early for the NFL draft.

In the flurry of private workouts that followed, Beason developed a liking for several teams, including Carolina and the New York Giants, and a dislike for a couple of others. One of the teams he didn't admire was New England. Beason felt the Patriots weren't loyal enough to their veterans; plus he didn't like the weather and didn't want to play in coach Bill Belichick's 3-4 defensive scheme.

Belichick came to Miami to work out safety Brandon Meriweather and Beason individually. From other former Hurricanes, Beason knew that Belichick would concoct a difficult workout.

“So he was just trying to kill us,” Beason remembers. It was then that Beason tried to gently sabotage his chances with New England.

Remembers Beason: “I said, ‘You know what, Coach? I need some water.' I knew he wouldn't like it. Brandon was like, ‘C'mon, Beast!' But I stopped and got some water.”

On Draft Day, 2007, New England picked 24th, right in front of Carolina after the Panthers traded down. Both Meriweather and Beason were still available. New England picked Meriweather (now a backup safety).

That left Carolina, at No.25, to take Beason. When his name scrolled across the TV screen, Beason felt a part of the NFL for the first time. “I didn't think I would cry,” Beason says. “But I cried, man. I cried like a baby.”

‘A pro bowl linebacker'

Beason irritated some of his veteran teammates with an eight-day contract holdout at his first training camp in 2007. Says Diggs: “I had a misconception. Because of the holdout, I thought he was one of those prima donna guys. Then I met him.”

Diggs and Beason bonded quickly – they now live in houses next door to each other. “He had his head on right when he got here,” Diggs says of Beason. “He played his butt off in that first camp, and he's still playing his butt off now.”

Beason began his rookie year starting as an outside linebacker, taking the injured Diggs' spot. When middle linebacker Morgan got hurt early in the season, the Panthers tried the rookie in the crucial spot.

Beason learned the new position quicker than anyone could have imagined. He was faster in pads than he was on a track. At 6 feet even, he wasn't as tall as the prototype middle linebacker. But Mills – the best inside linebacker the Panthers have ever had – was only 5-9. And, like Mills, Beason seemed to never get caught out of position.

By the end of the Panthers' disappointing 2007 season, Beason had become the bright spot. He was runner-up for NFC Defensive Rookie of the Year to San Francisco's Patrick Willis.

As a rookie, Beason set a Panthers team record for tackles. He is on pace to break it this season. “Beason is a Pro Bowl linebacker right now if you ask me,” Tampa Bay coach Jon Gruden says. “He's their heart and soul.”

Beason stays on the field for every defensive snap. Adept against both run and pass, his goal is to eliminate his mistakes completely.

What motivates Beason?

He wants to win the championship he never did in high school or college. He would like to be a consistent Pro Bowler. He would like to serve as a role model for children. And he wants to set down deep roots in Charlotte. He wants to be gentle away from the game and beastly while playing it.

“I like to be a ‘moment' guy,” Beason says. “People say things sometimes and it's a lot of hot air. I want to be in the moment – always. To be spontaneous. To enjoy what I'm doing right then.

“I want what I say to mean something.

“And I want my life to mean something.”

(charlotteobserver.com)

I

I