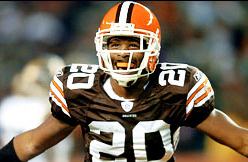

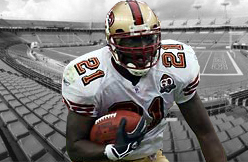

It was Thanksgiving morning 2007, and the Washington Redskins were preparing for that Sunday's contest with Tampa Bay. Santana Moss was sitting in a meeting room next to the NFC interception leader, a physical safety who had missed a game with a sore knee, and would be missing another.

"And he went down the line, 'Hey, Happy Thanksgiving,' to every coach," Moss recalled this summer. "I kept looking at him, and saying to myself, 'You don't have to do that, Sean.' But that's him. And then that weekend came, and boom, he was gone. Those moments I think about to this day. Who would have known, man, that was going to be his last week with us?"

Who can believe that it's been two years?

That weekend, right after Thanksgiving, Sean Taylor returned to his Palmetto Bay home, not far from the fields where he made his football name for the Gulliver High and the University of Miami. He had come to continue recuperating from the knee injury, and wasn't supposed to be in the house with his fiancée Jackie and their 18-month-old daughter, also named Jackie. During the second break-in of the month, an armed intruder shot in. Twenty-six hours later, Taylor's life ended. The legal proceedings seemingly never do. Five men were charged with a role in the murder. The trial has been delayed three times and one suspect who pled guilty has since petitioned the court to withdraw his plea.

But this isn't a commentary on the legal system. Nor is it designed as a tribute to Taylor's football exploits, since those are understood. It simply serves as a second attempt to tell a man's story. Taylor's murder was a tragedy for his family, friends and fans. It was a dark hour for the media as well. We were at our absolute assumption-making, narrow-minded worst.

You might remember bigots on anonymous message boards characterizing Taylor as just another thug who couldn't outrun his troubled past. But many media commentators, including prominent African-American columnists at major American newspapers, initially suggested Taylor's associations (from shady friends to the University of Miami itself) played some role in his fate. Many observers applied stereotypes that didn't fit; Taylor wasn't some abandoned inner-city male but, rather, a police chief's son. And while he had made mistakes, showing some poor sportsmanship and getting arrested twice (once for DUI and once on gun charges after his ATVs were stolen), he wasn't killed for his failings.

He was killed for his success, for what he had earned that others wanted. He died trying to protect what he most valued: his family.That got lost in the one-dimensional portraits. That's what still bothers former teammates, such as Moss.

"Once he passed, I just hated to hear people in the media say, 'That's the life he lived,'" Moss said. "No, he didn't live that life. That guy barely went out. He is a guy that did less than what I have done, when it comes to how I hang. The trouble didn't come my way. I have been brought into a lot of situations, but I have found a way to get out of it or found a way to turn my back. And I am thankful for that. But he was one of those guys that when the trouble came, it hit him, it hit him hard. And he got labeled for some of the stuff that he had been involved with, or some of the situations he put himself in. But as far as his life, and who he was as a person and who he was as a teammate, they didn't do a great job of really searching and seeing who this guy was before talking about him."

Even Moss, though, had needed some convincing. Moss played at a different Miami area high school (Carol City), and preceded Taylor with the Hurricanes. They finally became teammates in 2005, when Taylor was in his second NFL season, and started sitting together on planes.

"I had a perception of him, too," Moss said. "I didn't think he was no bad guy. I was just like, this guy, the way he plays football, he's one of the guys you don't really want to have a conversation with. So I had to kind of let him open up to me first. We started talking about music. And the music he was talking about, I just didn't put that music with him. And I'm like, OK, man, Sean's all right, man. He's somebody you can talk to."

Taylor's depth would have surprised most. Most, after all, didn't hear Taylor's lengthy and personal radio interview six weeks earlier with the Redskins flagship station. In response to a question about his fears, he replied, "You can't be scared of death. When it's that time and it comes, it comes."

The week before Thanksgiving, as they rehabbed together in the training room, Moss and Taylor had their own lengthy, very personal conversations.

"`Wow,' I was saying to myself," Moss said. "And I wonder if it was a sign that it was his time, he was ready to go because he was talking about stuff that wasn't on a level with what we had ever talked about. But he was on some off-the-wall stuff, and it was all great things, you know, just life."

A life cut too short, two years ago.

(sun-sentinel.com)